After the Storm

“I boarded the king’s ship; now on the beak, now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin, I flamed amazement: sometime I’d divide, And burn in many places; on the topmast, the yards and bowsprit, would I flame distinctly, then meet and join. Jove’s lightnings, the precursors o’ the dreadful thunder-claps, more momentary and sight-outrunning were not: the fire and cracks of sulphurous roaring the most mighty Neptune seem to besiege, and make his bold waves tremble, yea, his dread trident shake.”

– Ariel, from The Tempest by William Shakespeare

It’s been a busy couple of months at Output Arts HQ: in early December we showed our new audiovisual installation Storm at Enchanted Parks in Gateshead. This was a new commission by Newcastle Gateshead Initiative as part of this six night winter light festival in Saltwell Park. The theme of Enchanted Parks for 2016 was “A Midwinter Night’s Tale,” an imagined Shakespearean world marking the 400th anniversary of his death. We decided to take the opening magical storm of The Tempest as our starting point, and to recreate the drama and excitement of a thunderstorm.

We were partly inspired by a new relationship that we have formed with curators at the British Library. As well as being a famous repository for books, the British Library archives an enormous collection of sound recordings. Our initial interest was in how we might contribute spoken word recordings that we have made in the past, from artworks such as Lost and Sound, and are about to make for a new oral history project with Stoke Newington Literary Festival. However, we discovered that the library also has a huge set of recordings of the natural world — apparently more recordings of frogs than anyone could imagine! So we set-to listening to field recordings of thunderstorms; there is something equally thrilling and soothing about a proper storm — the hiss of rain and low murmuring of distant thunder interrupted by the sudden wild crash of a nearby lightning strike.

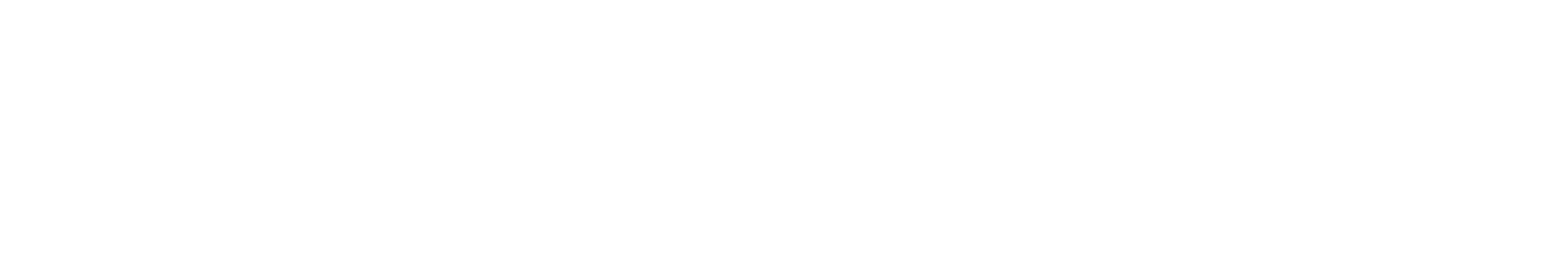

We knew that we wanted to make a thundercloud that hung above the audience; something that one would approach, pass threateningly close to and then look back on as it recedes into the distance, mirroring the experience of a storm passing overhead. We watched videos of lightning flashing inside dark clouds and knew that this is how it should feel: weightless and yet terrifying in its contained potential. However, we wanted to avoid making something that was too obviously like a real cloud.

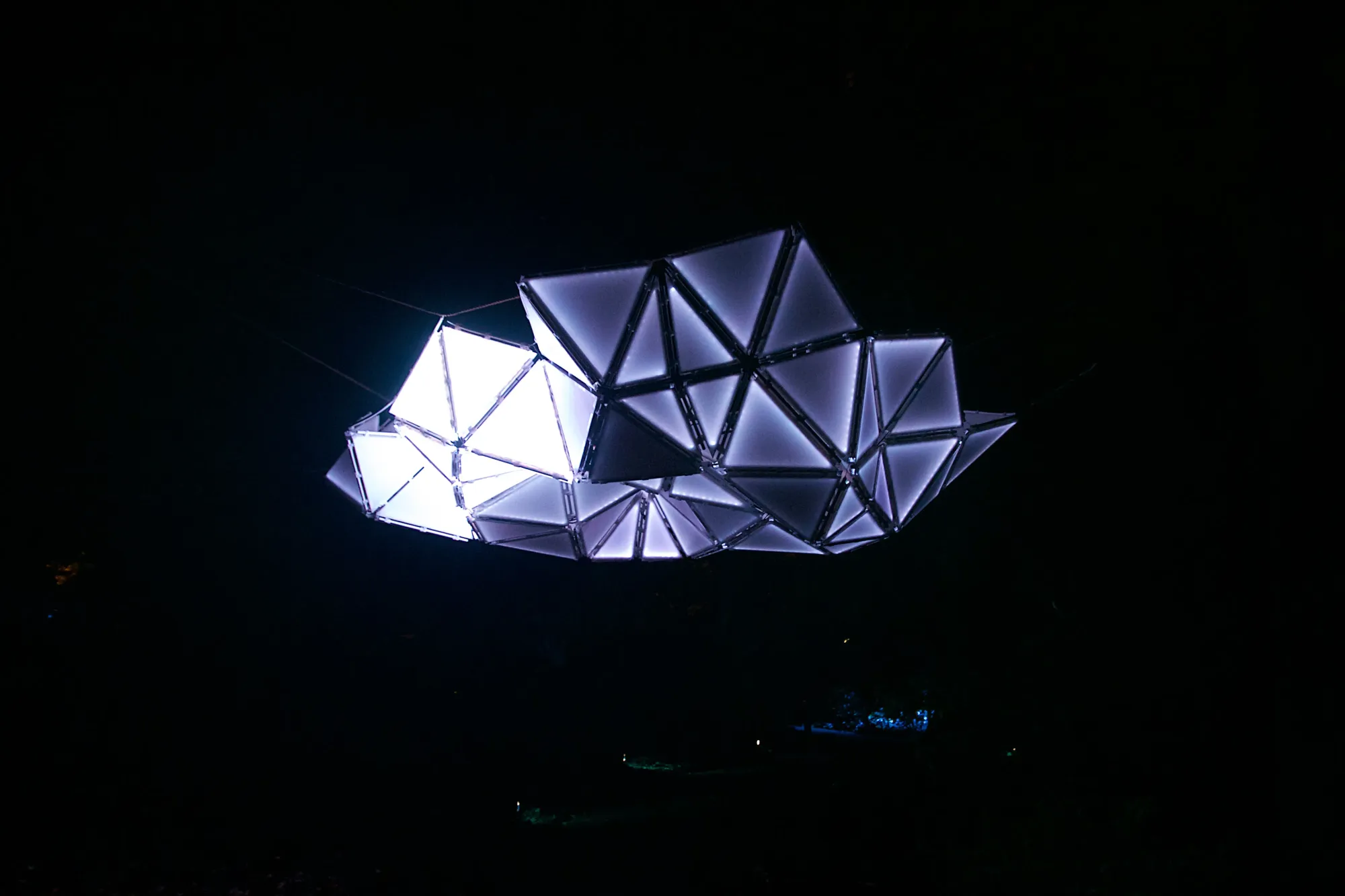

In miniature, a cloud begins to look like cotton-wool or a pile of old duvets; our thundercloud would have to be more angular and jagged to match the threat of the sound. We decided upon an arrangement of triangles akin to a simple geometric computer rendering of a cloud. To allow us to animate light moving inside the cloud it was going to be necessary to literally fill the structure with computer-controlled lighting, and these days that means LEDs — a lot of LEDs.

Although it wasn’t our intention to be deliberately misleading, we had a lot of people who saw our work-in-progress pictures on our Facebook page and told us how much they were looking forward to seeing our colourful installation. RGB LEDs are pretty much the standard controllable kind one can buy in bulk. I quickly decided that using the different colours provided an easy way for me to differentiate between the different triangles in each panel that shared a lighting controller, and check that they were wired-up the right way around and in the right order.

This made for some great pictures, but for the actual installation, there was only one colour that really worked the way we wanted it to: white. Funnily enough, I had been originally keen on having some colour in the installation and Andy had been pretty sure it should be white. However, when we got it all working with the thunderstorm sound recording and turned off the lights in the studio, I was instantly sure that it had to be white and Andy started entertaining the idea of it having some colour! Still, having the capability to produce something as brightly coloured as you see in the picture above has already given us ideas for future variations, so watch this space…

Making large technical audiovisual installations is challenging in its own right. However, making them suitable for showing outdoors in December in the north of England is a whole additional set of challenges. Ironically, our biggest problem with constructing our pretend storm would be making something that had a decent chance of surviving a real one. This entailed testing different materials, adhesives and techniques under extreme conditions: submerging sealed electronics overnight in a large bucket of water in the studio or leaving samples of stuck bits of plastic in the freezer at home. We eventually figured out what would work and how we could construct our cloud in such a way that it could be flat-packed for transport and then flexibly snapped-together and adapted on-site. Now all that was needed was to scale up the prototype to the real thing.

At this point it became apparent that our ambition for the piece was greater than the amount of time left to complete it without help — lots of help. We’re used to mostly muddling along on our own in the studio, but we weren’t going to finish Storm without drafting in some additional hands. Thankfully, our friends rose to the occasion, resulting in the most collegial piece we’ve ever made: in total we had 15 different people working on the piece to some degree over the month it took to complete. Managing a large project involving multiple people at different times, large quantities of materials and a complex sequence of build steps is always a bit stressful, but having so many great people working with us really made the project something special for us. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to our merry band of elves.

In numbers, the final piece comprises:

- 4320 LEDs;

- 23 square metres of corrugated plastic sheeting;

- an embedded Linux PC and 11 micro-controllers;

- 335m of cabling;

- 149m of trunking;

- 81m of pipe; and

- 936 clips to hold it together.

In addition we managed to get through 10 rolls of high-strength gaffer tape and an astonishing 13 tubes of silicon sealant! At peak the installation draws 900W of power, which is pretty bright for LED lighting.

For the geeks in the audience, the installation uses per-panel control boxes that drive each panel of 12 triangles using an AVR microcontroller (i.e., an Arduino — but with the software written in plain C). Each of these is hooked up to one of a pair of RS485 serial buses connected to the central computer; this can send control packets to the panels at 50 frames per second with colour information for the LEDs. The control boxes also distribute power to the LEDs, with each panel drawing a peak of 20A(!) of low-voltage current when flashing bright white. The main software is all written in Python (my weapon of choice, although with a smattering of Cython in places for performance) and the flickering and flashing of the triangles is driven by the storm audio as it is played — so rather than scripting an animation, the visual effects are triggered by detecting the amplitude of the thunder and rain, allowing Andy to focus on editing the audio.

Installing a new work for the first time is always a little fraught with drama — especially when you’re doing it a few hundred miles from home, outdoors, in Winter. The Enchanted Parks technical team were great, though, and worked as hard as they could to support us through hefting the piece up into the trees and a last-minute sound system panic.

The event was a great success for us. Around 30,000 visitors attended over the six nights and we received some great feedback on social media. You can see loads of pictures of the event on Instagram, where we seem to have been vying with the beautiful A Rose By Any Other Name by Cristina Ottonello and Exit, pursued by a bear by University of Sunderland student Jonny Michie for most-photogenic piece. It was great to hang out with the other artists and site crew leading up to the event, and our first experience of on-site catering!

We’re really looking forward to showing Storm again and have already started thinking about collaborations with other artists, much as we did with VOX and BREATHE festival; do get in touch if you’re interested. A final thanks are due to sound recordist Simon Elliott, who graciously allowed us to use his field recording of a thunderstorm in Gosforth, Newcastle in 2012 for the piece.

And here’s a video of the piece in action for you to enjoy: